Frank Dumont's "History of Minstrelsy from 1843 to the Present Time"Frank Dumont, a white performer, manager, and composer, was an active participant in the minstrel culture of the late nineteenth century and was involved in many shows in the Philadelphia area. Dumont continued to perform in and manage minstrel shows until his death in 1919, long after they had reached their peak in popular culture. In 1899, he published the Witmark Amateur Minstrel Guide to educate his fellow performers about the finer points of minstrelsy. The Guide contained skits, jokes, and songs featuring stereotypical black characters, as well as instructions on how to apply blackface properly.

In the years following emancipation and the rise of the Republican Party, audiences for minstrel shows dwindled and minstrel troupes had to alter their shows as new political standards dictated entertainment trends. Black minstrel troupes, which became increasingly more common, earned success and acclaim during Reconstruction. Thus minstrel troupes managed by white men and employing derogatory stereotypes nevertheless became the means by which many blacks entered the entertainment industry. Twentieth-century minstrelsy, and later vaudeville, showcased the talents of many black performers, like comedian Bert Williams. Even early movies like The Jazz Singer, which was done in blackface, had roots in minstrelsy, and varying forms of blackface and minstrel-like shows persevered in American popular culture until the mid-twentieth century. Dumont's "History of Minstrelsy" provides ample opportunities for research into this complex social phenomenon. Because the volume encompasses several decades of minstrel performances, it is possible to trace minstrel troupes (and sometimes individual performers) over the course of many years. The hundreds of programs and broadsides that are included indicate not only the content of the minstrel shows, but also how they were advertised and promoted to the public. Photographs of white performers in blackface, wearing tattered clothes and confused expressions, clearly evidence the racist attitudes that minstrelsy embraced. Dumont's notations and text provide an insider's perspective of minstrelsy's evolution and its place in the history of American theater. Due to its extremely fragile state, Dumont's volume is currently unavailable for research. A pending grant application would preserve this volume and make it once again accessible. Please stay tuned for further developments and feel free to contact Rachel Onuf, (ronuf@hsp.org) the Director of Archives. For more information about minstrelsy: http://www.s-line.de/homepages/jscheytt/minstrelshow/minmain.html http://www.africana.com/Articles/tt_200.htm Bean, Annemarie, ed. Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy. Baker, Houston A., Jr. Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. Dumont, Frank. The Witmark Amateur Minstrel Guide New York: M. Witmark & Sons, 1899. Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Mahar, William J. Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture Related collections: Minstrel and Variety Scrapbook, c. 1880, HSP Scrapbook Collection The following is the introduction to the volume by Dumont. Minstrelsy!! On this day - June 28, 1902 I am able to write in this; my history of minstrelsy - the undisputed fact that minstrelsy sprang from the circus. I have the programs and data to prove the assertion. The reader will carefully note all the circus programs herein inserted for the origin and rise of minstrelsy. All authorities are agreed that Brower, Emmitt, Whitlock, and Pelham were the originators or rather founders of minstrelsy. Charley White in 1860 wrote an article for the "N.Y. Clipper" in which he gave the history of the four originators – I have in this book an autograph letter from old Dan Emmitt relating the same incidents. The reader will find this letter in pages of this book – with these facts to begin with it is easy to trace the four men prior to 1843. Each negro dancer with the circus had a musician to play for him – a violin or a banjo. Brower had Emmitt with his violin or banjo. Whitlock played the banjo for Dick Pelham to dance and sing. The above circus bills will show Brower and Emmitt with the circus in 1840 – Emmitt playing the banjo for him. In January 1843 – Pelham had a benefit at the National Theatre (Chatham Theatre) and the four men mentioned arranged to give their circus songs etc. with four. This was an immense hit – a novelty – and captured the town. Next night they played at the Bowery Amphi Theatre. The first bill (benefit of Pelham) is in this book – also the 2nd night – from which I traced up minstrelsy to the present time. Daddy Rice and others appeared in black faces and sang, danced, or played in farces as individuals but it had no bearing upon minstrelsy save as suggestions which the four originators used individually in their circus experience – the fact remains [from the programs and bills] and dates upon them that minstrelsy had its inception in the circus. |

|

About the Mellon Project | Current Pick | Past Picks | Return to HSP.org © 2001 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Send comments about this site to webmaster@hsp.org |

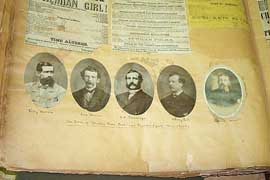

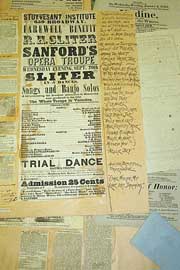

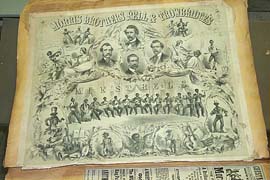

Dumont also collected programs and memorabilia pertaining to minstrelsy, and in 1902 he created an enormous volume (33"x24"x4") of approximately 200 pages that emphasized minstrelsy's ties to the circus and documented the history of this musical and cultural phenomenon. Pasted into this volume are circus broadsides, advertisements for minstrel performances, sheet music, programs, and photographs of performers (without blackface), many of whom are identified in captions. Dumont's compilation includes programs and advertisements for many of the most popular minstrel troupes and provides an extraordinary record of minstrelsy from the 1840s until the twentieth century.

Dumont also collected programs and memorabilia pertaining to minstrelsy, and in 1902 he created an enormous volume (33"x24"x4") of approximately 200 pages that emphasized minstrelsy's ties to the circus and documented the history of this musical and cultural phenomenon. Pasted into this volume are circus broadsides, advertisements for minstrel performances, sheet music, programs, and photographs of performers (without blackface), many of whom are identified in captions. Dumont's compilation includes programs and advertisements for many of the most popular minstrel troupes and provides an extraordinary record of minstrelsy from the 1840s until the twentieth century. The American blackface minstrel show was introduced in the 1840s, principally by three white men, Thomas Rice, Dan Emmett, and Edwin P. Christy. These men began their careers by joining the circus and performing tunes in blackface. Rice usually performed alone, while Emmett and Christy formed minstrel troupes. All three had traveled in the American South at some point, and created material for their acts by observing, exaggerating, and exploiting southern slave songs and dances. Minstrel shows became an extremely popular form of mass entertainment, especially in urban areas. A typical show expressed political themes that had close ties to the Democratic Party: anti-temperance, territorial expansion, and a pro-South stance that justified slavery and depicted blacks as innately inferior to whites. Minstrel shows, which were especially popular in the north and on the frontier, helped to solidify Democratic ideology in these areas during the crucial decade before the Civil War. Mass entertainment became the means by which Democrats could propagate their party's principles and manipulate the public's perception of slavery. Minstrelsy's negative depiction of blacks and sympathetic view of slaveholders encouraged white audiences to be conscious of color distinctions, not class barriers, and by doing so created a forum in which northern and western whites could identify with southern slaveholders.

The American blackface minstrel show was introduced in the 1840s, principally by three white men, Thomas Rice, Dan Emmett, and Edwin P. Christy. These men began their careers by joining the circus and performing tunes in blackface. Rice usually performed alone, while Emmett and Christy formed minstrel troupes. All three had traveled in the American South at some point, and created material for their acts by observing, exaggerating, and exploiting southern slave songs and dances. Minstrel shows became an extremely popular form of mass entertainment, especially in urban areas. A typical show expressed political themes that had close ties to the Democratic Party: anti-temperance, territorial expansion, and a pro-South stance that justified slavery and depicted blacks as innately inferior to whites. Minstrel shows, which were especially popular in the north and on the frontier, helped to solidify Democratic ideology in these areas during the crucial decade before the Civil War. Mass entertainment became the means by which Democrats could propagate their party's principles and manipulate the public's perception of slavery. Minstrelsy's negative depiction of blacks and sympathetic view of slaveholders encouraged white audiences to be conscious of color distinctions, not class barriers, and by doing so created a forum in which northern and western whites could identify with southern slaveholders. Before the Civil War the typical minstrel troupe consisted of four to six white men playing banjo, tambourine, bones, and fiddle or accordion. Minstrels usually came from middle-class urban families in the mid-Atlantic or Midwest. Donning flamboyant costumes, outlandish wigs and black makeup, often made from burnt cork, these clownish performers entertained audiences by singing, dancing, telling jokes, and performing skits. Some shows featured dapper men in blackface, representing northern blacks, as well as more disheveled and tattered men who personified common perceptions of southern slaves. Songs and dances often caricatured slave culture, and performers sang and spoke with exaggerated southern "slave" dialects. Minstrels usually depicted the stereotypical "happy darky," completely satisfied with his subservient role and too foolish to deserve better. Minstrelsy contributed greatly to the popularization of characters like Zip Coon and Jim Crow and perpetuated the notion that blacks were lazy, thieving, simple-minded tricksters. Tunes like Stephen Foster's "The Old Folks at Home," portraying slaves "still longing for the old plantation," were typical of the minstrel programs. Many other songs that eventually became part of mainstream culture, like "Dixie," originated in minstrel shows.

Before the Civil War the typical minstrel troupe consisted of four to six white men playing banjo, tambourine, bones, and fiddle or accordion. Minstrels usually came from middle-class urban families in the mid-Atlantic or Midwest. Donning flamboyant costumes, outlandish wigs and black makeup, often made from burnt cork, these clownish performers entertained audiences by singing, dancing, telling jokes, and performing skits. Some shows featured dapper men in blackface, representing northern blacks, as well as more disheveled and tattered men who personified common perceptions of southern slaves. Songs and dances often caricatured slave culture, and performers sang and spoke with exaggerated southern "slave" dialects. Minstrels usually depicted the stereotypical "happy darky," completely satisfied with his subservient role and too foolish to deserve better. Minstrelsy contributed greatly to the popularization of characters like Zip Coon and Jim Crow and perpetuated the notion that blacks were lazy, thieving, simple-minded tricksters. Tunes like Stephen Foster's "The Old Folks at Home," portraying slaves "still longing for the old plantation," were typical of the minstrel programs. Many other songs that eventually became part of mainstream culture, like "Dixie," originated in minstrel shows.